The Covid 19 pandemic has regularly been referred to as an ‘existential crisis’. Although it is often unclear exactly what the writer means by this statement, it has certainly been true that the Covid experience has brought existential issues such as uncertainty, anxiety, time and temporality, meaning, authenticity and relatedness more to the forefront for individuals and organisations. These issues have all come into sharp focus during the pandemic and must be considered by leaders in their future planning. Here I intent to merely highlight a few existential areas which leaders need to address. I welcome a deeper debate.

Existential themes

The business world, with its five‐year plans and milestones, and the conventions of an office based 9–5 business model, has been severely tested by the pandemic. Most plans are based on an assumption that although things will change, there are some core elements of stability. Who would have thought that highly desirable business properties would be closed and shuttered and standing idle for months on end? The fact that many businesses have survived, with staff working from home, is something which has surprised many, and raised questions as to how businesses may look in the future.

The Existential Leader – An Authentic Leader For Our Uncertain Times

By Monica Hanaway. Published 2019 by Routledge © Routledge

It has been an anxious time for business leaders and unfortunately the impact of the pandemic has resulted in many established businesses going under and many people losing their jobs. This has been an emotional experience for many people. For some, it has meant the loss of the identity they invested in their work status. It has caused individuals to question who they are without their professional label, and perhaps to question for the first time their authenticity, self‐identity and set of values and beliefs. Some have felt trapped and mourned the loss of the freedom they believed their salaries afforded them. Without the security of work, they may have felt they were unable to fully carry out their responsibilities to themselves and their families and so felt disempowered, vulnerable, and afraid. Many may previously have sought their sense of purpose and meaning in the workplace and without their daily schedule had to consider what really was meaningful for them. The not knowing when or whether they would return to their previous positions has brought them truly in touch with uncertainty and caused anxiety.

Their sense of time may have shifted. Some may have felt liberated to be away from tight schedules. They may have stepped back and looked at their previous lives and questioned whether they ever wish to return to cramming themselves in overcrowded rush hour tube trains to get themselves to a building where they would remain throughout the day before heading home on another overcrowded train. They may have embraced the freedom to go for a walk or to eat at times of day to suit their own, rather than other people’s schedules and wonder how they can ever return to the time structures they had previously accepted. Others may have experienced the loss of structure as frightening.

Existential thought does not allow much space for certainty, but we can be fairly sure that the day offices do reopen, and people return to the workplace, it will not be ‘business as usual’ or a return to ‘normal’. Both the people and places will have changed as a result of the Covid experience. This experience has meant that people have had to engage with existential issues they may previously have avoided. Leaders need to focus their attention more on these existential challenges if their businesses and organisations are to flourish post Covid. Let us look briefly at some of the implications of these issues.

Uncertainty

People may have consciously encountered real uncertainty for the first time during the pandemic, bringing with it feelings of powerlessness, making it difficult for them to connect with their essential freedom. During the pandemic, we have been required to live with uncertainty, to an extent which may previously have felt unbearable. Surviving this uncertainty can bring with it a greater understanding and belief in personal freedom and responsibility for self. The ‘certainty’ their previous job seemed to promise with its long‐term plans and pension provisions may have proved uncertain, and the false belief in the security it represented may provide people with a rationale for taking more risks in the future and possibly placing authenticity and meaning higher than security. Of course, the taste of uncertainty may have proved so painful for some that they will attempt to seek out more certainty going forward.

All leaders must consider the relationship with uncertainty that their returning colleagues will bring with them, and how this will be effectively built into new ways of working. Leaders will need to identify those who have flourished without the previous constraints, and who may have newly identified creativity and an increased comfort with uncertainty which can serve the development of the organisation. To ignore this is to risk these people will become bored and seek stimulation in other more progressive organisations. There will be other people who are longing for a greater sense of certainty and security and leaders must also consider how they will address this.

Temporality and Time

The general level of anxiety has increased as people have been brought into a more overt relationship with the temporality and vulnerability of existence. Some individuals may have faced the death of loved ones, often without the opportunity for a face‐to‐face goodbye. They may have authentically considered their own death for the first time. They may also be grieving other losses; they may have lost their job, relationship, plans or self‐concept.

Time may have taken on a very different ‘feel’, as stuck in lockdown, the days may have been hard to distinguish one for the other so it may have felt a long time since they have seen friends or ventured out to their workplace. Day has followed day, week has followed week, and we find a year or more of our lives has passed in a very different way from how we may have expected. Time may have been experienced as standing still, going very slowly or even racing by. The subjective nature of time will have been brought into sharp focus for many people.

Some people may be seeking longer term security and looking for permanent contracts and stability whilst others may have come to believe this is no longer a possibility and have come to embrace a more peripatetic ‘portfolio’ style of work. Leaders need to consider how they will meet the needs of both views which may require radical changes in how their organisation operates.

Meaning

An enforced disengagement from the daily schedule, which people may never have given much time to considering before, has led people to need to engage more fully with the question of what is meaningful. Their previous occupation may no longer provide meaning and so they may question whether they wish to return to their old job or look for a new more meaningful pathway in life. Leaders will have to consider the place of meaning within their organisation.

Relatedness

Our ways of relating to others has changed. Others may be seen as the potential threat to life, silently infecting us with a deadly virus. We no longer spontaneously greet people with hugs or kisses, we strive to keep at least two metres away. We have found new groups to divide into, e.g. those keen to be vaccinated v anti‐vaxers; mask wearers v those who refuse to wear them; those who stick to the rules v those who challenge or break them. How we work to remove the alienness of the Other when it is safe to do so will be a major task for workplaces on both a psychological and practical level.

Although productivity may have been maintained whilst working from home, the interaction with others and the possibility of spontaneous creative conversations has been lost. It is these unstructured conversations which often lead to the most innovative ideas. Without them, is there a danger that businesses become stuck with the status quo?

Authenticity

Being true to oneself and one’s values and beliefs is an important element of existentialism. Our beliefs and values may have shifted during the Covid experience and re‐entering the ‘new’/’old’ life may present challenges to our authenticity. People may have expectations drawn from their pre Covid interactions which will need challenging and in doing so provide opportunities for creative dialogues and different ways of doing things. On a personal note, it is often the shift in organisational values which has led to me leaving organisations.

Freedom and Responsibility

The pandemic has been experienced by some as a loss of freedom. This is true in relation to what we may or may not do, but throughout we have retained the freedom to think and make our own decisions. Some have experienced an increased sense of responsibility, particularly in relation to protecting the health and wellbeing of others. Businesses must address the increased awareness of these issues in a positive way. They must be ready for challenges to the old boundaries in freedom and responsibility with some individuals seeking more freedom and others craving more structure and less responsibility and freedom.

Existential Dimensions

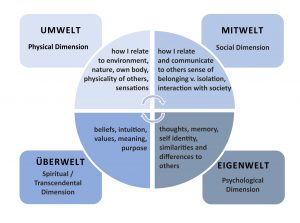

We do not always feel the same, or act the same, in all contexts, choosing to share different aspects of ourselves with different people, and in different contexts. These contexts can be grouped into four dimensions of human existence – the physical (known as the Umwelt), the social (Mitwelt), the personal (Eigenwelt) and the spiritual (Uberwelt). Readers coming from a business leadership background may see the connection between these dimensions and Deal’s (2003) four frames of organizational behaviour used in ‘Reframing Organisations’ which consisting of the structural, human resource, political and culture.

If a leader reflects on these dimensions, they may offer relevant questions which may help in preparing for a post Covid world, or at least one in which the pandemic is under enough control for a resumption of business.

Physical/Umwelt

In the physical dimension which is concerned with physical well‐being –

- How does your organisation relate to the environment – workplace, landscape etc?

- How do you look after the physical needs of your staff?

- To what extent will environmental changes need to be made in light of the Covid experience?

- How comfortable are people in their own bodies, do they have an increased fear of illness etc?

Social/Mitwelt

In the social dimension which is concerned with relatedness to others –

- How will you encourage social interaction and communication?

- How will a sense of belonging and relatedness be developed?

- How will you enable people to feel safe in their interactions with others?

Psychological/Eigenwelt

In the psychological dimension which is concerned with emotional and mental well‐being, with mental health issues expected to rise considerably due to Covid experiences–

- How will you take care of the psychological needs of your staff?

- Do your mental health/well‐being policies and practice need revision?

- How will you address people’s anxiety regarding travel to work, being with others, perceived loss of skills or confidence etc?

Spiritual/Uberwelt

In the spiritual dimension which is concerned with values, beliefs and meaning –

- Does your organisation show and develop its beliefs, values, meaning and purpose?

- Are these clearly evidenced in your mission statement and daily practice?

- Is there the potential to involve the staff in a review of these, in light of the pandemic?

If people have new foci of meaning (e.g. greater interest in the environment, development of meditative and other practices through lockdown) how will these be embedded in organisational thinking, planning and practice?

Business leaders may find it helpful to use these existential themes/givens and the ‘existential dimensions’ as a framework for preparations for reopening business.

About the author

Monica Hanaway is an executive and leadership coach, business consultant, mediator, psychotherapist, and trainer. She has authored The Existential Leader, An Existential Approach to Leadership Challenges, and Handbook of Existential Coaching Practice. She is passionate in her mission to bring existential thought beyond the academic arena into the business and wider world, believing it has much to offer in these uncertain times. She is perhaps the most prolific author in the great britain when it comes to existential issues.

I recognised myself in much of this, not because I am a ›leader‹ but because it speaks to all of us on different levels. This is such a great example of how our relationship with with uncertainty, time, freedom, identity and responsibility has been highlighted by this pandemic and the experience of lockdown.

I wonder if this experience will have taught us to be more accepting of uncertainty and the part it plays in our lives?

Dear Diana,

we honestly feel very happy about this very first comment on our still so young blog page. Thank you very much for your appreciative feedback. We believe that fundamentally existential questions will continue to come into focus in these times. This conviction is a major motivation for this blog. Thank you very much again!