The framework: Four existential dimensions in an organisational context

Contents

The framework: Four existential dimensions in an organisational context

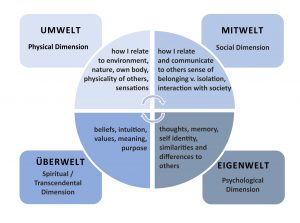

One way to explore existential issues pragmatically is through the framework of the so‐called four existential dimensions. These ›realities‹ represent tensions and apparent paradoxes that the (each) individual faces within the four dimensions of human existence: issues of the physical ›Umwelt‹, consequent issues of the social ›Mitwelt‹, inner and very personal aspects of the ›Eigenwelt‹ and the so‐called (spiritual) ›Uberwelt‹, representing the meaning‐seeking human being. Man’s existential issues are found in all these dimensions. We can identify one or more dimensions that are perhaps underdeveloped or within which conflicts (inner and outer) break out again and again and – especially in social systems – affect other dimensions as ’spillovers‹ and interact with each other. A good, life‐worthy and affirming state is basically achieved as soon as the human being has found a good balance of his or her answers to these themes of existence. As soon as changes, disturbances or impairments occur and are identified, the individual or a purpose‐oriented collective within an organisation can try to understand the situation with a view to the interaction of all dimensions. And they can take a stance on this and thus take responsibility for change and for a new balance.

The following diagram shows the existential dimensions within which we basically move in organisational contexts. Some dimensions will be fully and richly expressed at a given point in time, the individual or many will feel fulfilled in them, while other dimensions may appear as individually or even collectively quite unfulfilled within the organisation. Monica Hanaway (2019) has formulated these in terms of the organisational context:

Existencial Dimensions (see Hanaway, The Existential Leader, 2019)

I. Umwelt – the physical dimension

The physical dimension is concerned with how we respond to the ›Umwelt‹ and the natural world around us, each of which we are always already involved in. This includes attitudes to the body, the environment, the landscape, the climate, objects and material possessions or the body and bodily needs, health and illness and mortality. The dynamic within this dimension is between striving to master the elements and the laws of nature and the need to accept the limits of nature as given. Acknowledging that the security given in this way can only be temporary and accepting limitations as they are right now can bring great relief. (Hanaway 2019, 21 pp.).

In the organisational context, for example, acknowledging the factual belongs in this category: what is this organisation about, what is our mission, what is the corporate concern, what is actually needed here and now? Special challenges within organisations arise from this dimension due to the sometimes dramatically changing environmental conditions. This happens, for example, due to a massive increase in insecurity and complexity that penetrates from there or becomes apparent, which is reflected as a liquefaction of formerly supportive structures as special challenges and burdens within the once steady state of the organisation.

II. Mitwelt – the social dimension

Within the social dimension we relate to the behaviour of others in the world around us and what they embody. This also includes the impression they want to create with their appearance, their habitus, in order to distinguish themselves in a more or less subtle way within their belonging to the ›Mitwelt‹. This includes the ›communities‹ in which we live in and, for example, the social class, different ethnic groups, sexual orientations to which we belong. It also includes those who try to exclude us or whom we try to exclude on the basis of characteristics, so that we or they should not belong, on the basis of differences of origin, culture or stratification. The attitudes can range from love to hate, from cooperation to competition. The dynamic contradictions can be understood in the spectrum of acceptance and rejection or belonging and isolation.

Even within organisations, some people prefer to withdraw a bit. An astonishing paradox, however, is that even there, withdrawal and demarcation necessarily require ›Mitwelt‹ on the part of others. Others hunt for public acceptance and submit to the current rules and fashions of the moment. Still others try to rise above rules and role expectations, overstretch or exceed their competencies, or they take personal responsibility, e.g., in crisis situations, or they even bring about crisis situations in order to gain influence over others in this way or to gain dominance over others with other forms of power, at least temporarily.

Within organisations and teams, in addition to the hierarchical position someone occupies, one of the most important characteristics so far, which at the same time determines demarcation and affiliation, is that of professional qualification. This includes membership of so‐called ›professional fraternities‹ and specification (what am I looking at?), professional codes (think of the sometimes, desperate attempt to together with IT department staff solve a problem that is not personalised when you are the one sitting in front of the screen). This also includes the gender affiliation or attribution of integrating or disintegrating characteristics to the other within the ›Mitwelt‹.

At this point, it may already be indicated to pronounce, that a change in the external boundary conditions of organisations, which as a consequence entails the – strategically indicated – multiple diversification (professional, gender, ethnic, cultural) within top teams and organisations, is a task that will require coordinating processes and instances that integrate possible conflicts.

In the ›Mitwelt‹, encounters arise, existence is characterised by human togetherness. It arises through relationship and dialogue with others, through feelings of belonging and exclusion and the experience of loneliness. The ›Mitwelt‹ emerges through social interaction, intersubjectivity, participation and empathy and is equally shaped by these elements.

III. Eigenwelt – the psychological dimension

Within the so‐called ›Eigenwelt‹, the individual consistently refers to himself, and in this way he or she creates a very ›own‹ world. This includes views about one’s own character, past experiences, future possibilities. In addition, personal strengths and weaknesses are often experienced here. People seek an identity that comes from temporal congruence and consistency, the sense of being essential and having and being a self.

Within organisations, this experience is often closely linked to what is called a ›position‹. One then is ›clothed‹ within, one embodies it. Or the identification goes so far that it merges with one’s own person, with a sense of ›being‹ oneself. – Inevitably, in processes of change, there are many events that confront people with evidence to the contrary and plunge them into a state of confusion or incongruence, inconsistency and questioning of their identity and into despair. Building self‐affirmation and determination are as much a part of this as learning self‐distance and a dedication to and advocacy of a cause, a subject, a competence, a professionalism and expertise within the given organisational framework, without confusing oneself with the role or even the position.

IV. Uberwelt – the spiritual/transcendent dimension

Within the spiritual dimension, people relate to the unknown or even the uncanny to them and construct for themselves an ideal world, an ideology or a philosophical perspective from which they are also guided within their role as a member of an organisation and as part of a multiple top management team. »Man is a being in search of meaning«, says Viktor E. Frankl, referring to Plato.

In a sense, (self-)transcendence arises in relation to the ›Uberwelt‹. Here, man relates to something that is more than himself, without however – and this must be said quite clearly here – losing his identity in the collective experience of intoxication. This requires that he steps out of his self‐reference, e.g., by devoting himself to a creative task that corresponds to his role, which he has affirmed. This reference is expressed in intuition, convictions, values and the meaning that the person is able to give to his life and actions. In order to avoid a purely futile pursuit of desirable goals, the human being has to give his or her own answers to the questions of life. He or she alone is able to give »meaning« to life.

In view of multiple diversity, it should be obvious that precisely this – each person’s own answer – can lead to very different answers and frictions within a purpose‐oriented community of organisational circumstances of a top management team. In the common, reflective and dialogical understanding about the value of emergence, a common attribution of meaning develops within a top team and the respective advocacy for the overall responsibility. This emerges from the understanding that is generated about the respective complementary being‐in‐the‐world within the four dimensions and which only emerges through the joint assembly of the different pieces of the puzzle.

With the help of joint reflection on these existential dimensions and their effectiveness within organisational structures, a top leadership team can develop a good understanding of the sense of ›being‹ within all these aforementioned four dimensions that gives everyone a good place in them. This requires an understanding of themselves and others within it, acceptance and consideration of these existential ›realities‹ for all of us. This can give them a compass for how to orient themselves in the world as a team and how to relate to it, in all its complexity and the multiple diversity of their individual composition.

This is exhausting, and above all it is not a socially romantic event, because in this way very concrete inner, outer and factual conflicts also become apparent and have to be processed, which might create a sustainable consensus and which do not amount to lazy compromises, which can otherwise corrode the necessary trust in a common future and task.